Shell Rock, IA – November 2015 … This is part two of our ‘Featured Artist’ conversation with the celebrated music producer Michael Beinhorn, covering production concepts. Part III of our Michael Beinhorn series will break down the Courtney Love Wedding Day EP sessions.

Shell Rock, IA – November 2015 … This is part two of our ‘Featured Artist’ conversation with the celebrated music producer Michael Beinhorn, covering production concepts. Part III of our Michael Beinhorn series will break down the Courtney Love Wedding Day EP sessions.

If you’re interested in Michael Beinhorn beyond this article series, you can visit his website, or dive into his recently released book- ‘Unlocking Creativity: A Producer’s Guide to Making Music and Art.’

CL: It seems like you show up to a production, happily waiting to be surprised by what will develop, rather than force-feeding a ‘Producer’s perspective’ onto the project, i.e. there’s not a specific cookie-cutter template when working with you. However, you do have a production methodology, correct?

MB: Yes, there is always a methodology. First and foremost, I like to insinuate myself in a recording project, not only as someone with a lot of experience, but as a collaborator. I feel more at ease with this than the timeworn stereotype of producer-as-supreme-deity on a recording session. On one hand, I see the recording process as a series of creative tasks (as I’ve laid out here- “Reframing the Recording Paradigm“) that, when performed in an appropriate sequence, will yield the very best iteration of an artist’s work. At the same time, I visualize what the project feels (or “looks”) like conceptually. That may sound kind of abstract, but I always get an image in my mind’s eye of a project. I also like to treat the recording process as creative experience and the result of everyone working on the project, collaborating with one another to make something special and unique. These facets are mainly determined by the individuals involved and the music they are making. The varying degrees of those parameters, combined with a different cast of characters on every recording insures that each will be different from one another.

CL: Are you profiling the artist on multiple levels from the get go in order establish their custom production program tailored for them?

MB: From one perspective, you can say that. From another perspective, I’m learning about them so I can help them maximize their abilities in the best interests of the recording project.

CL: Would you say your process, though abstract, is hands-on when it comes to contributing artistically to the production?

MB: Yes, very hands-on. It’s more fun that way.

CL: When contributing to the production on an artistic level there’s a balance you have to find where you’re enhancing and not overshadowing the artist correct?

MB: Yes, that requires sensitivity and paying attention to the immediate landscape. If you’re sensitive to your own work dynamic and simultaneously, what the mission of the project you’re producing is, you can tell right away when you’ve crossed the line and are letting your ego run rampant. It’s imperative to always maintain priorities and let them be a deciding factor in every decision that gets made. A lot of really good ideas get tossed out, but the ones that stay must always be the most appropriate to what the project requires.

CL: So the golden rule is, the artist and what they’re trying render is always in focus; though you’re always looking for their truth as it were?

MB: How did you know this, even before I’d answered the previous question? You’ve got to be a mind reader. Actually, what the artist is trying to render is now multiplied by whatever you- and everyone else who is collaborating on the project- bring/brings to it, so in a sense, the project becomes an extrapolation of the artist’s original intent and a lot more. In this way, it kind of takes on a life of its own.

CL: And whatever the artist’s ‘truth’ is, there must be no boundaries to the creative process?

MB: Well, I’d certainly like to think so. Let’s put it this way- disallowing for boundaries (apart from what can subjectively be viewed as “appropriate” in the context of a given project) has always yielded the best, most exciting and inventive work, as far as I can see. And in the creation of any kind of music, those elements are incredibly important.

CL: Do you empathize with them and try to internalize that ’truth’?

MB: With the artist? It’s a different type of empathy, I guess- more like sensing or “feeling” the artist’s emotional state and finding the technical and creative means in myself that will best help them express that state.

CL: Is this what motivates a decision or the intent behind your production choices?

MB: Again, that really comes down to defining what the mission for a project is. Sometimes, that comes as a discussion with the artist before any work begins. Sometimes, that initial conversation with the artist, plus that “mental picture” of what the project will look like when completed, kind of guides me. Often, something the artist has said in passing stays with me and informs me about where the project needs to go. As an example, I’ve worked with several artists, each of whom told me they wanted their next recording to be their “Dark Side of the Moon”. That is a very general statement and can be interpreted in many different ways. However, in each case, I understood what that comment meant relative to the specific artist and let it form the basis for where the project went creatively.

CL: From your standpoint, are you trying to create or act as a conduit to capture the conviction of the feeling the artist is portraying?

MB: I feel like I have to be two distinct conduits in a recording scenario. One creates the space so the artist can express themselves fully through it. The other allows whatever ideas I can have that will improve the project to manifest themselves in the best way possible. Because so many ideas seem to come from someplace other than me, I try to be as open and receptive as I can to allow those ideas to come my way. To me, that’s part of the job of recording production, being the best possible conduit.

CL: So, as a means to an end, the tools of the trade, the microphones, preamps, compressors, EQ’s etc… are creative instruments in the production, not innocent bystanders. You have to commit to the sound, the devices and signal path that will yield the desired result right?

MB: Yep- that’s about right. I feel that a lot of people treat recording as a utility, a process incidental and entirely supportive to the end result of creating a recording. I say that’s only partly true, because the recording process itself- the entire soup-to-nuts process is inextricably tied into the end result of the recording and therefore, it defines that end result, sometimes, as much as the songs. Take a look at the previous recording I mentioned, “Dark Side of the Moon”. This is an indisputable masterpiece which is held up as a classic- not only in the art of popular music, but in the art of creative record making. Now, imagine what this record might have been like if Pink Floyd had decided they didn’t want to experiment, didn’t care how the record sounded and instead, felt they’d get the results they desired by banging the thing out in a few days. My point here is that the total process of making the recording- down to technical choices regarding microphones and compressors- all have a cumulative effect on the final product. These are conscious choices made by skilled technicians and they add up to create a unique body of work.

CL: When it comes to those choices and recording techniques, people often try to imitate this or that from X record in an almost monkey see monkey do… You can repeat a technique or signal chain, but to what end or purpose?

Technically repeating something others have done seems pointless without the impetus (Almost a simulation of process rather than an intent to create a emotive result.)

MB: I feel that repeating something you’ve heard is a great way to learn how to do it, but allowing that to be a defining characteristic of your work is really selling yourself short. I’m a big proponent of learning technique as thoroughly as possible in order to destroy the playbook and create your own new version of the language. This is the only way people progress and develop instead of plateauing and getting stale.

CL: How do you know when something’s not working?

MB: You can feel it. If you’re conscious and awake, you should be able to tell immediately or within a few moments, if something isn’t working. Recently, I was working with a keyboardist on a song with a chorus that was very hard to crack. He came up with a whole bunch of ideas- many of which were terrific- but in the end, we junked them all because they simply didn’t work. On average, it took a few seconds to a few minutes to make the call. It’s something you can feel in your body. the sensation of things not sitting right.

CL: Let’s talk more about music production from the technical side. You’ve been recording digitally for sometime now, do you use tape anymore?

MB: I haven’t used tape for a while now and the main reason has been logistic. The last recording I worked on was done in an automobile repair shop, which had been converted into a recording space and had no tape machine. Nearly every studio I’ve worked at within the past 7 years had no tape machine. Recently, I’ve been considering trying tape again, but it would have to be the right medium for the right project.

CL: From a DAW standpoint, are you working mainly with Pro Tools, or do use any other systems?

MB: I mainly use Pro Tools, because it’s ubiquitous, but I’ve used Nuendo (which I’m considering switching back to) and would opt for DSD in a heartbeat. It sounds magical.

CL: With your own rig, do you rely on a hybrid setup?

MB: It varies, depending on the parameters of the project I’m doing. I try to work according to what resources are available- not based on a template that I’ve become used to. At the high end of the spectrum, that could be recording through a console with analog decks and a Sonoma DSD system. At the low end, it could be recording through analog preamps without a console into a DAW and monitoring digitally from there. At the very least, I’ll use my Lavry converters for I/O and an external clock (as long as it’s relatively high quality).

CL: Is digital something you feel you have to live with, or are there aspects that you’ve come to rely on in your work, just as you would with an analog piece of equipment?

MB: I will be honest and say that while I enjoy certain aspects of PCM recording (such as the amazing transient response and convenience of use), I am not always partial to it. The only digital recordings I’ve done where I really enjoyed the end result was either using an old Euphonix R1 recorder (which was a real beast) with Lavry converters or in DSD. Whenever I A/B these recordings (or analog tape) to stuff I did in PCM, I always feel like something is tonally missing with the PCM. Based on budgetary limitations most projects are currently faced with and the ubiquity of the format, PCM digital recording is something I choose to live with. While it is not unpleasant, at least to my mind, it is not optimal.

CL: Speaking of converters, it seems all of them filter the sound to one degree or another, how did you arrive at choosing Lavry, extensive A/B tests, and what drew you to them?

MB: I started using the Lavrys when I produced Korn. It was very early days for the 96/24 format- there was really only a dedicated recording system- the Euphonix R1. Frank Filipetti and I did a bunch of shoot-outs between a few different converters (including the dedicated Euphonix converters) and determined that the Lavry Blues were the ones for our job. Frank and I both felt that the Lavrys had a nice punch to them, a good, solid low end and a pleasing aggressive quality. I still use them.

CL: Back to analog for a minute, you went to the extent of creating your own analog format, two inch eight track, what was the genesis for that?

MB: I always figured that was just common sense. I mean, 16 track 2″ at 15 ips sounds better and punchier than 24 track 30 ips, so it just makes sense that 8 track 15 ips must be even better. But, the machines I got were Studer 800 MkI’s, which only have 15/7.5 ips as speed options. I wanted the biggest, most extraordinary sound from a tape machine and I got it. At 7.5 ips, it was extraordinary- the absolute best recording format I’ve ever heard.

CL: You sold those machines right, whose got them now, and do you miss them?

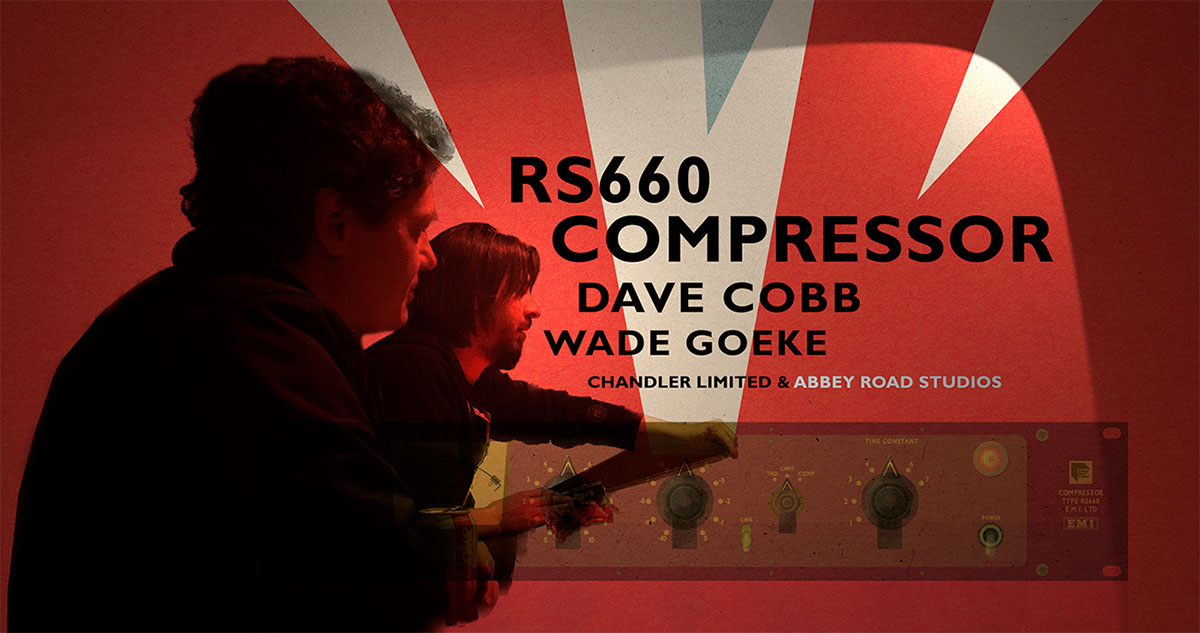

MB: Jack White has one and Dave Cobb has the other. I’m sad not to have those machines, but they belong with people who have studios they can live in. I did so much traveling with them- but they weren’t built to take that kind of abuse and they need regular maintenance. If someone else is enjoying them, I’m happy, too.

CL: Let’s talk about pre-production. How does pre-production with Michael Beinhorn at the helm shake out?

MB: This is really dependent on a lot of different variables- what does the artist want to achieve, what genre of music it is, how intense the arrangements are, what specific issues there are in the songs, my own vision for the artist’s music, etc. Generally, I’m working with artists who are incredibly talented and capable, but require assistance with the realization of their ideas, so I’m prepared to go as deep as possible to make everything work properly on a structural level. This requires a lot of in depth work and really challenging the artist to dig into their material and examine it from unfamiliar perspectives. I hesitate to say that I push artists to do things, but I do encourage them to explore, take chances and optimize their capabilities. Although nothing concrete- in terms of a finished recording- is derived from pre-production, it can be the most important stage of the entire project and defines what it will gel into. I feel anything less is selling the artist and his music short.

MB: This is really dependent on a lot of different variables- what does the artist want to achieve, what genre of music it is, how intense the arrangements are, what specific issues there are in the songs, my own vision for the artist’s music, etc. Generally, I’m working with artists who are incredibly talented and capable, but require assistance with the realization of their ideas, so I’m prepared to go as deep as possible to make everything work properly on a structural level. This requires a lot of in depth work and really challenging the artist to dig into their material and examine it from unfamiliar perspectives. I hesitate to say that I push artists to do things, but I do encourage them to explore, take chances and optimize their capabilities. Although nothing concrete- in terms of a finished recording- is derived from pre-production, it can be the most important stage of the entire project and defines what it will gel into. I feel anything less is selling the artist and his music short.

CL: From pre-production, do you come away knowing what sonic characteristic or texture you’re going for with each source, or is this something that happens organically during the recording process?

MB: To an extent, yes. Working with the music in a more analytic environment helps it take shape in my mind (and presumably, the artist’s). I can get a mental picture of what that looks like and how it can be achieved sonically/ technically. However, once in the recording environment, so many new variables enter the picture and my initial mental image can change on a dime. That degree of uncertainty is one of the things that makes recording music so much fun.

CL: Do you try to keep the characteristic or texture consistent throughout the whole of a record or are you always looking to change it up from one track to the next?

MB: My experience is that if you listen, each song tells you what it needs- in terms of sound, texture and orchestration. I go with what feels best, but because of the component of listening to the music in this way, I always feel that I’m getting directed, instead of making judgments.

CL: Is there anything or a specific source in the arrangement you consider sacred ground?

MB: The only absolute necessity in arrangement is that it acts as a supportive element and doesn’t distract from the song flow. Beyond that, I don’t feel anything else about arrangement or structure is sacrosanct or utterly essential. Pretty much, anything goes.

CL: With pre-production out of the way, day one in the studio, how do you usually like to start a session, is there a particular instrument you like to start building from and getting sounds for?

MB: Depends on the style of music, but if this is a rock record we’re talking about, then drums generally go first. I like to start with foundational elements and drums create the foundation. Once in awhile, depending on the artist, music being recorded or vibe being sought, we’ll try something different or record most of the band at once. On some projects, the drum performances sound better with the rest of the band playing, sometimes they sound better with just the drummer playing on his own.

CL: There’s a sense that you’re always working to capture the energy of the artist or band in the room at that moment, almost as if they were playing in front of an audience. On the first day of the Courtney Love session at The Atrium, I couldn’t help but notice the P.A. system in the live room, what was the concept behind that?

MB: Yes- I like to get as much energy in the performance as possible. Anyone who hears a recording, instinctively knows if the performers were present while they were recording- that is one of the sexiest things about listening to music that was performed. Using the P.A. (actually, it’s a sub-woofer array) as a real-time amplification source for drums, can be helpful in that process.

CL: So the sub-woofer array is present to create an extra dimension for the artists? How do you deal with any bleed in to the microphones, or do you let it become part of the track?

MB: I pray for bleed from the sub-woofer array into the microphones- especially those with very large diaphragms. That bleed is a gift from the gods, themselves. I live for it.

CL: With bands do you prefer to record live as much as possible, or track it?

MB: Depending on what the artist sounds like, sometimes it’s appropriate to track live or, to go for more detail in the recording, overdub the instruments and simulate a live feel. Whether or not the musicians can play their instruments, or play well as a group is a big factor in determining how to record them. I have an issue with the blanket aesthetic of tracking a band live, simply because there’s an unwritten law which states that music of a specific genre can’t possibly be any good unless it’s recorded exactly the way some mouldering band from the 1960’s did it (back when they didn’t actually have choices about how they recorded). Many bands sound great live, but the recording studio introduces new variables and can affect the performers- sometimes, adversely. My experience is, you need to have a solid ensemble sound to record in a studio as an ensemble or you need to be very seasoned. Or both.

CL: If you are tracking, do use initial live takes as a building block or scratch track to re-track?

MB: Once again, there can be multiple variables involved, so I try not to work by a playbook. More often than not, I’ll treat a scratch primarily as reference, but still get it sounding good in case it can be useful later.

CL: Are you more elaborate with micing drums, or do you prefer a less is more approach, treating the kit as one instrument while try to get the sound upfront rather than dealing with options later?

MB: I would love to say that I prefer simple drum micing set ups (just because it goes with a certain bad-ass rock and roll aesthetic) but I often find myself erring on the side of more is more. I like detail, depth, presence and staging- and while you can get an amazing drum sound with a pair of great mics, Perhaps, it’s a character flaw- I like the variables and hyper-reality that come from multi-micing a drum kit. I’ve also found this to be a solution for drummers who hit super hard and choke when they hit. Of course, as you add mics, you are also quantifying issues of phase, so you have to be careful.

CL: What’s your approach to tuning drums?

MB: Deep and open, with as much punch as possible. It’s a weird combination, because those variables often work against each other, but when you get them interacting in the right way, the sound is always compelling. To me, pitching the drums appropriately is really important.

CL: Do you ever replace drums?

MB: Only if there were 5 minutes to get a drum sound prior to recording. Or if using samples was the plan all along. Which means almost never.

CL: For bass guitar, do you tend to mic the cabinet, go direct or both?

MB: I’m a fan of both together. A bunch of mics, a great DI and usually some external processing, where applicable (like a DBX 120 XDS.)

CL: Do you have a favorite mic for bass cabinets?

MB: There are a bunch- usually a Neumann U47 works great- so does the AT 4047, AT5400 (the only issue is that it has a hard time with high SPL and padding it alters the tone too much), Sennheiser 421, etc. I like a speedy bass sound with a lot of depth, nothing too soft or spongy. Recently, I tried a Soundfield MKV and enjoyed it very much.

CL: While we’re talking about the low-end, do you ever engage in sub-harmonic processing, beyond what you get naturally from the bass?

MB: Yup- as mentioned above, I really like the old DBX 120 XDS. It’s not really a bass enhancer like the 120 X- it appears to synthesize a lower octave that tracks the input source. Used excessively, this can sound like a an octave divider pedal, but subtly, it adds a really nice, if unnatural low end presence to things (which is ok by me, because a sound doesn’t need to appear natural to be good).

CL: Let’s dig into electric guitar some… Do you have a standard, single or multi-mic setup you prefer, and what are mics?

MB: I generally enjoy multi-micing, as I don’t get everything I want out of one mic. So many mics work for this application- the old standard SM57, Royer 122 (because it translates the velocity of the sound), AT 4047, RCA BK5A/B, AT 5400, AT 5045, AKG 451, Sennheiser 421… etc (wow- I’m predictable). I generally don’t go in for room mics as they can be a bit too smudgy and blurred in the mids (although the tone can be quite nice if they are in a decent room) and the lack of distinction often fights with other sounds I want to be similarly focused.

CL: What’s your thought on stacking guitar tracks, is this something you do?

MB: If the project calls for it, yep- stacking works. Sometimes, it’s not appropriate, or I might just go for 2 if I want to go for separation in the guitar tones. People often think the guitar tones on “Untouchables” (Korn) is massively stacked, but for the most part, it’s just the two guitars, occasionally with some lead lines.

CL: Do you re-amp at all, or try to get the sound from the start?

MB: Nah- that’s never worked for me- the gain staging isn’t the same, so the sound invariably changes and gets flatter. if I haven’t nailed it the first time, I’ll generally start again from scratch until it’s right.

CL: Are guitar pedals used for post processing as effects during mix?

MB: No- I generally like to have everything as it needs to be prior to mix. If the mix engineer wants to try anything, I’m always open, but I try to have those bases covered before the process is finalized.

CL: Let’s take a moment to talk about keyboards. How has being a keyboardist helped in your productions?

MB: I have never been a technically proficient keyboardist (although, I’ve recently been digging into theory again. There’s always something new to learn). Having a basic grasp of keyboard hasn’t done a whole lot for my producing (frankly, I’d rather listen to Booker T. play B3 on a record I’m producing than take the time to get good enough that I can pull off a reasonable Booker T. facsimile), but having an understanding of chord voicing relative to keyboard (vs guitar, etc) has helped quite a bit. I fee it gives a better overview with respect to song arrangements.

CL: You must have quite a collection of vintage synthesizers, can you tell us more about them?

MB: It’s nice. I have a bunch of instruments- some classics- an ARP 2600, EMS Synthi AKS, a modular Moog system, MiniMoog, a Serge modular system, etc. These instruments are incredibly flexible- I could spend the rest of my life playing only them and the only reason I’d repeat myself would be due to my lack of imagination. I tend to use a lot of signal processing to mess things up further.

CL: Are there any modern synth’s that you’re digging today?

MD: I like the new modular stuff- there are so many boutique companies with specialty modules- I can’t keep up with them. I also like some of the software synths- especially stuff like the Thor in Reason, in particular, because the it’s not an emulation of an old synth and it has routing capabilities that are unheard of in analog world.

CL: It feels like you use synthesizers to create unique sounds the will only ever happen that one time, something special forever captured in that moment as it’s printed. Is this a conscious act, and what’s the thought behind it?

MB: Yeah- it’s conscious. If you’re using a modular synth for signal processing, etc, it’s kind of a one- shot deal, anyway. There are too many variables and even if you notate your patch and take pictures (unless there isn’t a lot to it), it will be hard to recreate. And then, there are other variables such as level fluctuations coming in, etc.. I love all that because it forces you to work without a net (stay grounded in your unconscious mind) and create sounds that are totally specific to whatever you’re working on.

CL: What are and some of the non-traditional ways you employ a synth in a production to achieve this?

MB: Most music I work on is not specifically synth-friendly, but there is room to use synths as sources for external processing. This takes sound modification into an entirely different- and interesting- realm.

CL: Can you give us a specific example from one of your productions?

MB: There’s a great deal of processed guitar on “Celebrity Skin”. Sometimes it’s not easy to tell because the tones just blend in really well with amped sounds. One very obvious use of this processing is on the title track. I was standing right next to the filter frequency knob on my Serge when the main processed guitar pass was ending. The guitarist’s note was just hanging there and I thought, “Why not?” Things like, that are part of what make recording so marvelous.

That’s it for Michael Beinhorn- “Harmonic Distortions Part II”, in the meantime don’t forget to check out Michael’s new book ‘Unlocking Creativity: A Producer’s Guide to Making Music and Art.’

In our next Michael Beinhorn installment we’ll fully dissect the Courtney Love ‘Wedding Day’ EP Session.